This post is part of the accompanying tips, resources, interviews with experts, and stories of recovery included in the exclusive serialization of Cured: The Memoir.

Dear Friends,

It’s not easy to talk about suicide, but according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), suicide rates in the U.S. increased between 2021 and 2022.

The five years I spent suicidal were excruciating—but not just for me. My mother (a true hero) endured five years of being on suicide watch. Families and friends are the heroes in these situations, yet they’re rarely given resources or training.

Friends, family, and anyone who needs support and/or wants to learn more about being there for someone experiencing suicidal thoughts can take the QPR Suicide Prevention course. QPR stands for Question, Persuade, Refer—the three steps to take when helping someone in crisis.

The QPR Institute is included in SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices and offers many courses. Its online, one-hour course specifically addresses how to assist someone in crisis, including

understanding the common causes of suicidal behavior

spotting warning signs of suicide (direct verbal cues, subtle verbal cues, behavioral clues, situational clues, etc.)

knowing how to get help for someone in crisis

The course gives specific examples of what to look for, say, and do.

One of the most powerful parts of the training is the list of suicide myths and facts they go over:

Myth: No one can stop a suicide; it is inevitable.

Fact: If people in a crisis get the help they need, they will probably never be suicidal again.

Myth: Asking someone in crisis about their thoughts, feelings, and plans will only make someone angry and increase the risk.

Fact: Asking someone directly can reduce anxiety and open communication.

Myth: Only experts can prevent suicide.

Fact: No, we can all help.

When I was suicidal, I was very aware of the myth that those who talk about it are just attention-seeking. I didn’t want to be seen that way, so I didn’t talk about it, which almost led to my death. As my instructor put it, it’s not attention-seeking; it’s attention-needing.

Anyone can take the training—organizations too. There’s a course for teens as well.

Readers like you make my work possible. Support independent journalism by becoming a paid subscriber for $30/year, the equivalent price of a hardcover book.

Visit the Table of Contents and Introduction of Cured:

Find more resources for mental health recovery.

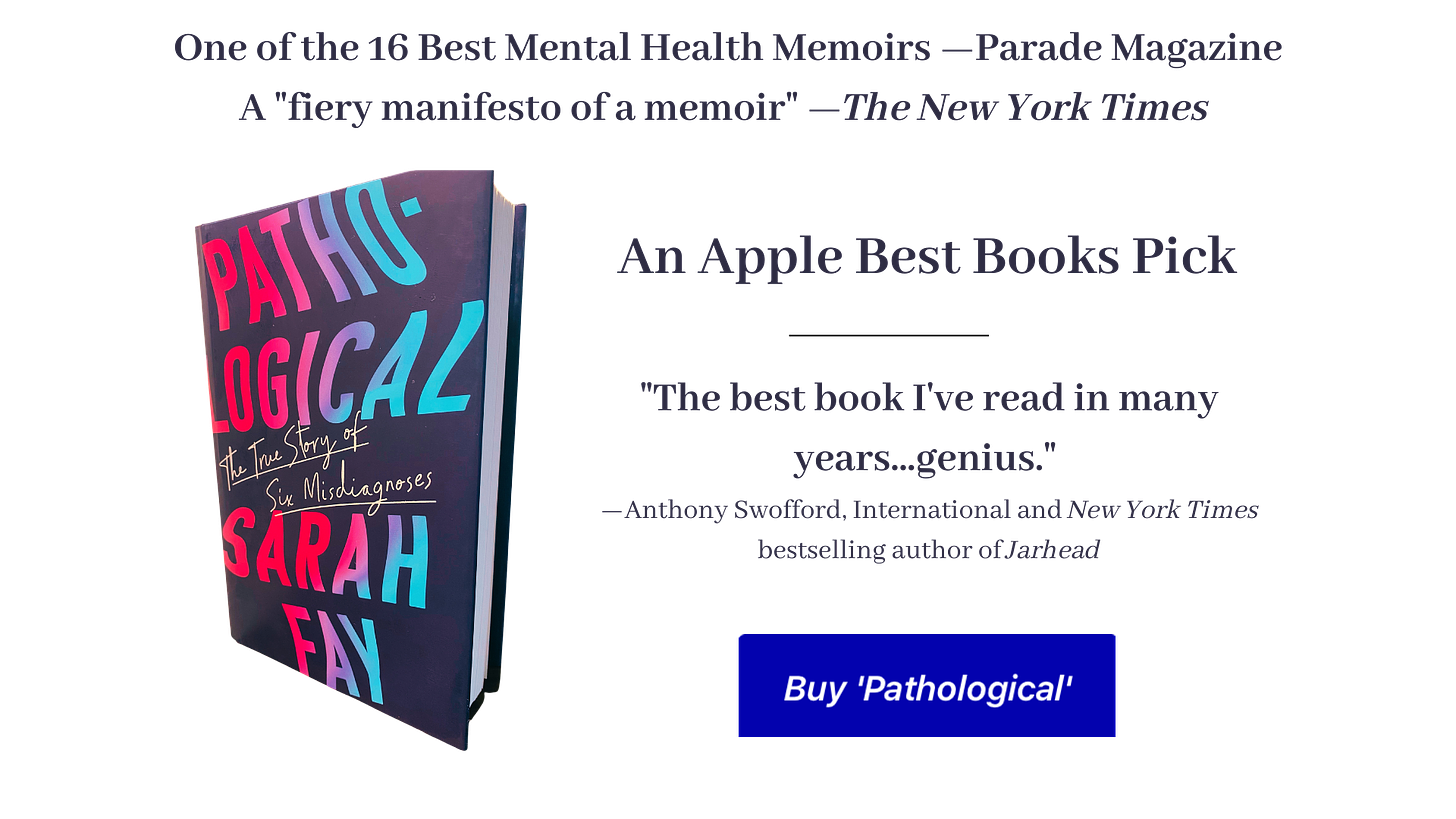

Read the prequel to ‘Cured,’ ‘Pathological’ (HarperCollins):

I agree that suicide is not inevitable. Intervention can change the course of events. I recently shared a story in my newsletter, Accidental Mentors, about how a friend’s mother’s rumored death by suicide impacted my life and made a big difference on 9/11. It was a tragic memory from my early teen years that stayed with me and motivated positive action to help prevent others from dying by suicide. https://www.annettemarquis.com/p/a-tragedy-that-saved-the-lives-of

I agree that suicide isn't inevitable and disagree that it's mostly preventable by these kinds of person-to-person interventions. The intervention training typically encourages uncertain supports to make referrals to crisis teams and inpatient services, and involuntary inpatient in particular tends to increase the odds of a suicide death after release. The potential for a confidant to call the crisis team (which can involuntarily commit you) reduces the odds that we'll confide in anyone because of the risks. I wanted to die on more than 7K days of my adult life; still living at age 66; but lost a career job to my one involuntary, had to quit a divorce support group that was really important to me after someone inappropriately sent a crisis team to the women's shelter where I was living, and feel like I lost a couple decades to meds-induced emotional fog.