What’s below—how we need more nature for all and less green for the elite few—comes from

who asked me to contribute to her Substack Going Gently’s wonderful Kissing the Earth Project.1 The project asks us to spend a little time in nature (though not all our time) every day in June.As I write this, jackhammering pounds in the not-so-distance, cars drone along Lake Shore Drive, a truck beeps as it backs up on the street below my apartment.

Chicago—cities in general—never quite feel like they count as nature or Mother Earth. So much concrete and scaffolding and drilling and hammering and trash and exhaust.

I’m privileged though—lucky enough to be able to cross the street and be in the lush green of Lincoln Park.

Every morning, I spend half an hour on the Nature Boardwalk, a Midwestern prairie ecosystem, complete with a (manmade) pond. The ecosystem teems with life. Sunflowers taller than me shade the path. Bullfrogs announce themselves with their foghorn-y call. A single white crane often sits on an island in the middle of the pond far enough away from us humans to believe he’s in “real” nature too.

Most people don’t have this luxury.

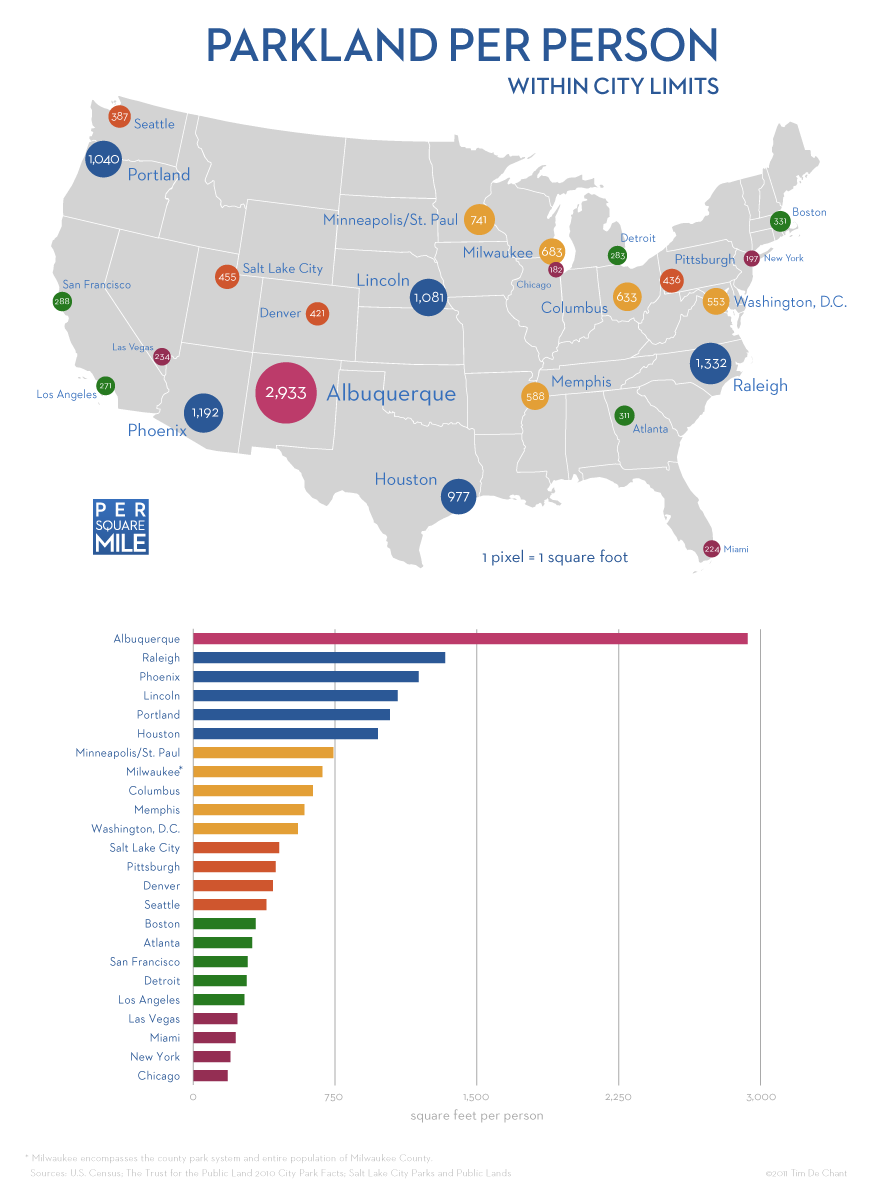

Chicago doesn’t make it easy for people in most neighborhoods to get even a dose of nature. I’ve seen this firsthand.

I teach at two universities in the city: Northwestern University (rated #9 in the country) and DePaul University (rated #151). Most of my Northwestern students grew up privileged amidst lush suburban lawns and SAT tutors and excellent high school teachers. Most of my DePaul students have none of that. They’re often first-generation college students from economically deprived neighborhoods with zero access to a decent education to even put them in the running for a top-ten university.

People don’t understand that perhaps 80 percent of students at top-tier universities like Northwestern aren’t necessarily smarter than those at bottom-tier universities. (This is a guestimate based on my ten years of teaching.) It’s more that top-tier university students were groomed to perform well in an educational environment and raised believing that formal education is crucial to success.

DePaul students are often from tough neighborhoods with little access to green space.

In one of my classes, I assigned the students a photo essay. They were to capture “their Chicago.”

One of my students, from Englewood (ranked #3 on Chicago’s list of the city’s most dangerous neighborhoods), started his photo essay with a photo of grass.

Just grass. Luminous green and spikey.

He’d taken the photo in the university’s small quad.

“We don’t have this in my neighborhood,” he said.

The students and I hadn’t been talking—we’d been listening—but the room felt heavy with silence.

Environmental inequality is more important for student success than it may seem:

Children who grow up in neighborhoods without green space are 55 percent more likely to develop a psychiatric disorder independent of other risk factors. That includes mood disorders like bipolar, psychosis, eating disorders, and substance use disorder (or substance abuse, depending on which term you prefer).2

Children diagnosed with ADHD experience milder symptoms if they have “green time.”3

Increased air quality has a direct relationship with student performance.4

This is all to ask, who gets access to nature and who doesn’t and to what effect?

The rich shall inherit the earth

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the rich have extreme access to nature compared to those who are economically disadvantaged.5

More nature! More Earth! More! More!

And all for me! Me!

In urban areas, the wealthy and educated have far more opportunities to be in green spaces compared to those who are economically and educationally marginalized.6

Private individuals and corporations own 60 percent of the United States, much of that concentrated in the hands of ten individuals and families, including Ted Turner (ranked #2 on the list of the top ten landowners in the U.S.).

Then there are the second, third, and fourth homes. On the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, more than 90 percent of beaches are privately owned, often by the ultra-rich. The rich and luxury hotels own 60 percent of Sarasota, Florida’s beaches.

Some of those beaches are patrolled by security guards who tell interlopers that if they pick up a shell, it’s stealing.

It definitely could be considered stealing but not from the wealthy property “owners.” In Sarasota, the land actually belongs to the Calusa, Tocobaga, and Timucuan Native tribes. This is the same situation in the Hamptons, most of which belongs to the Shinnecock Indian Nation, and Cape Cod, which is the ancestral land of the Wampanoag.

Luckily, wet sand belongs to all of us; it’s just that we can’t cross privately “owned” dry sand to reach it.

Fresh air may soon be the privilege of the .1 percent with multi-million dollar apartments with state-of-the-art filtration technology in the U.S., affluent-only air-filtered spaces in India, and “lung wash” vacations for the wealthiest in China.

The rich siphon what’s left of the natural world for themselves yet ironically, they’re the ones driving climate change. From Oxfam:7

In 2019, the super-rich 1 percent were responsible for more carbon emissions than 66 percent of humanity (5 billion people).

Emissions of the richest 1 percent will cause 1.3 million heat-related deaths between 2020 and 2030—roughly the equivalent of the entire population of Dallas.

Since 1990, the richest 1 percent have used up more than twice as much of the carbon budget as 50 percent of the world’s lowest-income population.

We could argue that this is the consequence of capitalism and what’s done is done.

Unless we want a world of mentally healthy people.

Your mind on nature

If we go by the numbers, 23 percent of Americans have been given a psychiatric diagnosis and declared to have any mental illness (referred to as an AMI by the National Institute of Mental Health) and another 5 percent have received a diagnosis that indicates serious mental illness (SMI).

Add to this the fact that according to the Environmental Protection Agency, Americans spend 86 percent of their time indoors.8

The medicinal effects of nature and being outdoors on our mental health are both obvious and compelling:

Being outside in nature improves self-esteem, social skills, and emotional regulation.9

Getting “green exercise,” i.e., off the treadmill and out of the weight room and simply walking outside, can have large benefits on mood and self-esteem.10

Nature can indirectly affect mental health because it makes us feel primally connected and gives us an increased sense of belonging.11

The one drug it seems we haven’t tried to treat mental illness? Blades of grass. Someone should bottle and sell it.

More access, less greed

We don’t need a lot of nature. Even looking at an indoor plant can reduce stress and improve memory and focus.12

A little goes a long way, but we don’t need to gobble up land for ourselves. Green and blue spaces (bodies of water) can be for everyone.

Every afternoon, I walk the lakefront, even when it’s ninety degrees with ninety percent humidity and (mostly) when it’s below zero and the windchill whips against my face.

On those walks, I forget my student and how fortunate I am to be near 1,180 cubic miles of fresh water, crisp blue or pewter grey depending on the sky. Nature in all its massiveness. Lake Michigan doesn’t have the vastness of the ocean, but it’s 22,300 square miles and fifty fathoms deep. I don’t know what a fathom is, but fifty of them sounds deep.

Today, if we’re in a green or blue space, even if it’s just near a plant, let’s consider ourselves lucky. And maybe that bit of green or an expanse of green is enough.

Sending you less of more! more!

Sarah

P.S. If you’re new here, Less and Less of More and More is a community of people who want a little less in a culture of too much—less stuff, yes, but also less of the pressure to have more! more! Join us to get a monthly reminder of less like this one (less in your inbox) and a monthly community thread where we talk about something we’d like a little less of in our lives.

P.P.S. My cat Sweets is a fresh-air addict. He’d spend every minute on the balcony if he could.

“Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood,” Uppsala University, Sweden, 2019.

“Could Exposure to Everyday Green Spaces Help Treat ADHD? Evidence from Children's Play Settings,” University of Illinois, 2011.

See this excellent, deeply researched article by Substack writer and AstraZeneca scientist

.“Rich” is a relative term. There seems to be no agreement on the exact income and net worth that qualifies you as “rich,” but if you have more than $4,000 in savings, you’re richer than half the world’s population. Generally speaking, you’re in the global 1 percent if you earn more than $60,000 to $90,000 a year after taxes (single, no children). In the U.S., that jumps dramatically. To be an American in the 1 percent, you need to earn somewhere around an average of $400,000 a year after taxes ($600,000 for a household). To be in the .1 percent in the U.S., your net worth needs to be $25 million whereas in India, it’s a scant $60,000 to $900,000.

This is a harrowing and important article: “The Nature Gap: Confronting Racial and Economic Disparities in the Destruction and Protection of Nature in America,” Cap20, 2023.

“The Carbon Inequality Era: An assessment of the global distribution of consumption emissions among individuals from 1990 to 2015 and beyond,” Oxfam and the Stockholm Environment Institute.

“Indoor Air Quality: What are the trends in indoor air quality and their effects on human health?” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“Flourishing in nature: A review of the benefits of connecting with nature and its application as a wellbeing intervention,” International Journal of Wellbeing.

“What is the Best Dose of Nature and Green Exercise for Improving Mental Health? A Multi-Study Analysis,” Environmental Science & Technology, 2010.

“Exposure to natural space, sense of community belonging, and adverse mental health outcomes across an urban region,“ Envrionmental Research, 2019.

“Effects of Indoor Plants on Human Functions: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses,” International Journal on Environment Research and Public Health, 2022.

Excellent and so well researched essay on a topic I care deeply about, and appreciate what you shared about Sarasota's beaches as I live in nearby Venice and see the miles and miles of coastline owned by the rich and the hotels. Thank you for the reminder of the original tribes who actually own the land. The inequality around green spaces concerns me deeply, too. I would love to see our city planners consider how to extend green spaces into those neighborhoods which lack them. When I was young, my mother was part of the Fresh Air Fund, providing "country vacations" to some of New York City's neediest children, although in our case it was a couple of weeks on suburban Long Island. I saw through the eyes of Tommy, who stayed with us a couple of summers when I was eight and nine, that what I took for granted in our grassy lawn and safe playgrounds and neighborhood pool was a wide-eyed wonder for him. I am glad to see the Fresh Air Fund still exists but it would be far preferable that youth in inner cities could have their own versions of fresh air in their own neighborhoods.

Good morning Sarah,

I agree with your post as a matter of public policy. At the same time I'm one of those miscreants who enjoy ready access to nature by virtue of where I live. I grew up going to a beach club near Deal, NJ, now use the beach in East Hampton and in Manhattan I live next to Central Park.

Over the longer term, there has been an enormous improvement in US Air Quality thanks to the EPA.

https://gispub.epa.gov/air/trendsreport/2023/#introduction

But these are averages and the quality varies according to the socioeconomic character of the neighborhood. As well, you make an excellent point about indoor air quality, which should be a much higher priority on payback alone and of course on moral grounds as well.

Indoor air quality is even worse in the developing world where cooking is often done indoors using wood and other unhealthy energy sources.

One issue to keep in mind: housing is expensive because of zoning. If we build more parks, that will further reduce land that could be used for housing development. And if we increase density in a place like NYC, then the sq. ft. of green space per capita will go down.

Finally, East Hampton parking passes are indeed prized possessions. And if you park on streets close to the beach you'll likely get a ticket. So while the beaches are public, they're really not accessible to everyone.