Can Meditation End Mental Suffering?

Can Meditation End Mental Suffering?

I met the late Thich Nhat Hanh in 2010 when I interviewed him at his monastery in Southern France, Plum Village. I wasn’t Buddhist, and I wasn’t much of a meditator.

Not that I hadn’t tried. Since being told I had major depressive disorder three years earlier, I’d searched for my “inner body” with the spiritual-teacher (and multi-millionaire) Eckhart Tolle while lying on the floor. I’d mindfully washed my hands and done the dishes just as the American-mindfulness-proselytizer John Kabat-Zinn instructed. I’d pretended to be dead in savasana and ohmed with my palms pressed together “in prayer” in yoga class after yoga class.

It all seemed to have the opposite effect to what was promised. Body scans were a harrowing, claustrophobia-inducing nightmare. “Watching my breath” made me hyperventilate. “Being mindful” garnered me an additional diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Thich Nhat Hanh would change all that.

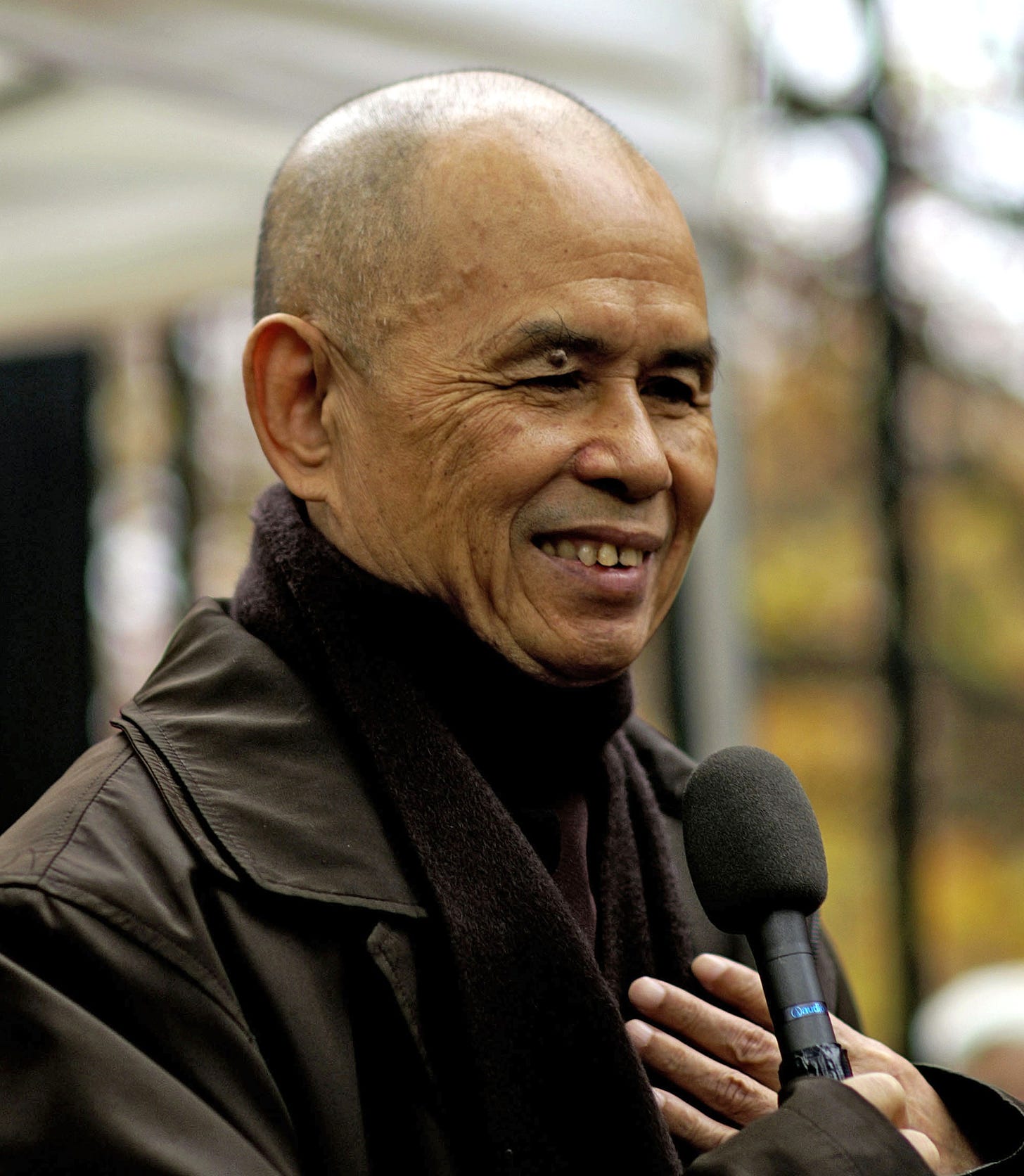

Hanh was a celebrity-Buddhist. Though he lived at Plum Village in France, he toured the States nearly every year, giving lectures and making television appearances. He had nine other community retreat centers, located in the United States (New York, Mississippi, and California), Hong Kong, Australia, Thailand, Germany, and elsewhere in France. He’d published over thirty books, many on his imprint, Parallax Press. Oprah had interviewed him.

As one of the founders of the mindfulness movement that was everywhere in the U.S., he made meditation accessible. Until the 1970s, the Buddhist practice of meditation was primarily a scholarly area of study. It took hold as a practice—something Americans tried to do—in part because of the 1975 publication of Hanh’s book The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation. It was all about the present moment: walking, drinking tea, breathing. No need to leave your comfortable or uncomfortable life and enter a monastery; just pay attention, live in the present moment.

The editors of the magazine I’d pitched the interview to hadn’t said yes, but they hadn’t said no either. As an interviewee, he didn’t quite fit the magazine, which tended toward modish filmmakers, hipster novelists, edgy poets, and sullen musicians, not earnest, enlightened monks. But the editors said they’d accept it, assuming the result was “right for the magazine.” I’d paid my own way and gambled that they’d publish it. Hanh’s representatives had accepted the invitation. It seemed unlikely that they’d ever heard of the magazine. The name of it—The Believer—may have led them to think it was more spiritual than it was.

Still, part of me had pitched the idea of interviewing Hanh because I wanted him and his brand of mindfulness meditation to cure me. The blackness in my stomach had disappeared and materialized again. I’d spiraled into what seemed a wheel of darkness. As much as I wanted a diagnosis, I didn’t want to take medication and had never called the psychiatrist Dr. W had referred me to. Hanh could make me feel whole again. In his books and lectures, Hanh promised inner peace and joy (which I translated as the total absence of discomfort) and relief from conflict, suffering, and stress.

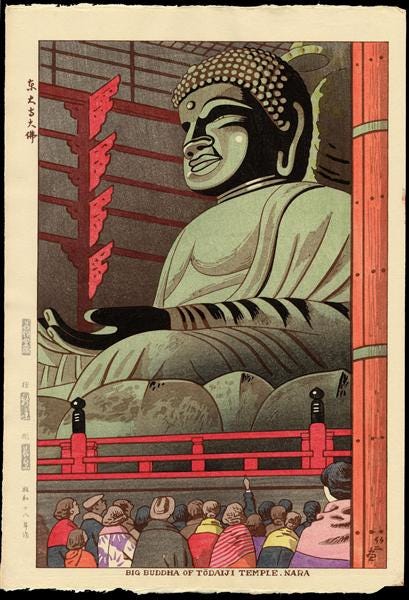

I visited Plum Village in the fall when it wasn’t open to guests. They’d made an exception for me because I’d be interviewing Hanh. It was rainy and cold. Yellow and red leaves lay on the dying grass. In the distance was a red-roofed pagoda with a large statue of the Buddha seated in the lotus position. The monks lived in Upper Hamlet, which consisted of a series of white stone houses with tiled roofs; the nuns lived in Lower Hamlet, most of them in a single stone building.

The first night at dinner, about twenty nuns sat on the benches in the small dining hall. It smelled of brown rice and sesame oil. On a row of long tables was a buffet of large steaming pots and trays of food. There was a stack of plates and a basket of chopsticks on the buffet table. I took a bowl and chopsticks and stood behind two nuns in saffron robes.

The nuns went through the line, scooping rice and vegetables and tofu. They didn’t fill their bowls to the top. In one of his books, Hanh explained the practice. The Chinese name for the alms bowl that Buddhist monks carried with them as mendicants literally translated as “instrument of proper measure.” A heaping bowlful meant not practicing right view, right intention, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, or right insight. And if you complained about not being able to overserve yourself, you could add not practicing right speech.

The food, I knew, was organic, sustainably grown, and vegetarian. Hanh wrote about “eating anxiety” and “eating anger”—literally. When we ate chickens that had been kept in cages, he said, and were so furious they tried to peck to death the chicken in front of them, we are their anxiety and their anger, too.

I made my way through the line, scooping rice and vegetables into my bowl. As someone with an enthusiasm for sugar, I was disappointed, though not surprised, we wouldn’t be finishing our meals with a treat.

I sat at one of the long tables on the bench with the nuns. They ate slowly and efficiently. Each bite was just the right size. No more, no less. Meals were eaten in silence. I couldn’t detect even the faint sounds of chewing and swallowing.

Hanh advised that we chew each bite of food fifty times—fifty times. The point was to enjoy, but not swallow the food until it liquefied. I could barely chew into the double digits before gulping it down.

As I brought my chopsticks to my mouth, a bell sounded. The nuns stopped and put down their eating utensils. I almost continued when I remembered reading about Hanh’s mindfulness bell. Anytime a bell rang—the phone, an email chime—we were to stop and inhale and exhale three times. We were to enter and inhabit space, the space between the bell and the action it signaled.

Breaks, in my world, weren’t necessary. Or, at least, I didn’t care for them. Gaps—space— made me too aware of myself. Still, I breathed in and out with the others, trying but failing to find a sense of calm.

After dinner, I went to my room, sat on the floor, and, using the futon as a desk surface for my laptop, started to generate extra questions for my interview with Hanh.

As an interviewer, I over-prepared. I read as many interviews with him as possible and recorded the questions he’d been asked a million times, so I didn’t repeat them and could get fresh responses instead of pat answers. (Anyone, even a monk, who’d been interviewed too many times gave rote replies.) Rarely did I ask the majority of the questions I’d written down. They were a security blanket, a way to avoid silence, dead air.

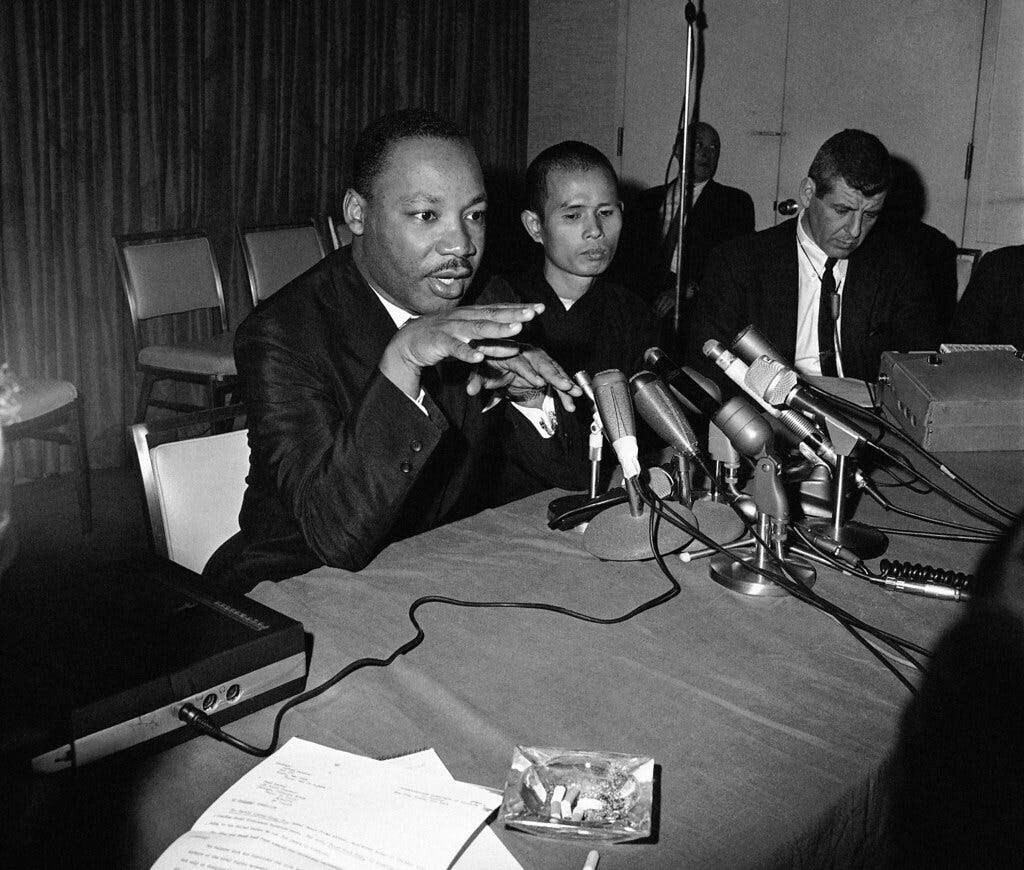

I’d read everything I could find about and by him. Born in 1926, he became a monk at sixteen. During the Vietnamese War, he founded Engaged Buddhism, a movement that took him out of the monastery and into public life to lobby for peace. Martin Luther King, Jr., nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize, calling him “an apostle of peace and nonviolence.” Hanh returned to Vietnam but continued to speak out against the war. In 1967, he was exiled from both North and South Vietnam. After lecturing and teaching in France for the next eight years, he began the process of establishing his monastery, which, with over two hundred monastics and ten thousand visitors each year, was one of the largest in the West.

I waited for a knock on my door from one of the nuns to inform me when my interview with Hanh would be. I was only scheduled to be there for six days, which didn’t seem like a very long time. No knock came.

I looked back at the computer screen. A blank new page stared back at me. Space. Writing began without space or punctuation, with no signposts or guides to aid communication. Words butted up against each other, making even the most elegant thought look like gibberish. Over the next couple hundred years, the practice of putting dots between words and then spaces to clarify finally took hold.

Thinking that someone must have forgotten to inform me of when I’d be meeting with Hanh, I got up and went downstairs. It was after nine p.m.

No one was in the dining area. I went into the kitchen. No one was there either. I worried that they’d forgotten about my interview.

On the wall hung a chalkboard on which was written a list of names and chores. There I was: Sarah Dinner dishes.

The next morning, I rose at 3:30 a.m. to make it in time for morning meditation with the others. I dressed and slipped into my boots. In the cold and the dark, I went down the steep stairs and outside. My feet crunched against the gravel road as I followed several nuns to the meditation hall.

No one spoke. No one directed me where to go or what to do. I sat at one of the empty spots. Should I use the cushion or the bench? On the cushion, I arranged myself not in lotus but cross-legged and waited. My visit was arranged on the condition that I’d participate in life at the monastery for the six days I was there. I’d be one of them.

A gong sounded. The meditation session began. While the nuns meditated around me, I closed my eyes and focused on my breath. In and out. In and out. No sense of ease passed through me. My shoulders remained hunched. Instead of deepening, my breath grew more and more shallow. Soon, I felt as if I wasn’t getting any air.

I opened my eyes and gasped. Trying not to make any noise, I breathed in—desperately, anxiously. My eyes remained open for the rest of the session. To fill the time, I counted backward and forward, to and from five hundred, which was a kind of meditation, I supposed.

When the gong finally sounded, I extended my numb legs. They woke, sparking pins and needles. It was some time before it passed, and I could stand.

We ate breakfast in silence. Because no visitors were there, there weren’t activities for lay practitioners like me. While the nuns studied for an hour or two, I wrote in my room.

Though I intended to work on the introduction to the interview that still hadn’t happened, I sat staring at what little I’d written. After a period, I’d typed a single space. When I’d learned to type, I was a double-spacer. Later, I found that doing so was incorrect; one space follows a period. In typing class, I worked on an actual typewriter. My teacher didn’t tell us that we only double-spaced after a period because a typewriter used monospaced fonts (all letters are the same width) and required a double space to make a document easier to read. Computers use proportional fonts (an ‘i’ is narrower than an ‘r’), so the visual break isn’t necessary.

That afternoon, after lunch in silence, we sat in the meeting hall on cushions on the floor. On a stage sat a television and an old VCR. One of the nuns put in a videotape. Onscreen came Hanh seated cross-legged on a similar stage. He looked young, maybe twenty years old.

Why were we watching a videotape? I glanced around. The nuns were focused on the TV.

In the recorded talk, Hanh was difficult to understand at first. His Vietnamese accent made his voice sound watery. He spoke slowly, spacing out his words in unfamiliar ways.

He told a story about the Buddha and his monks meeting a villager who’d lost his cows. I didn’t get the gist of the tale until Hanh explained it: Possessions are burdensome. He went on to say something else I didn’t catch. Then he said that each person has the Buddha inside her. He went so far as to say that if you have mindfulness, concentration, and insight, you’re a Buddhist.

When Hanh’s talk ended, I was led outside to help move sandbags to the base of one of the buildings, ostensibly to protect against flooding. I did as I was told. No task at the monastery was completed in a hurried manner. The nuns picked up the sandbags with purpose and walked seeming to feel each step.

That night, I waited—through dinner—but no one approached me about my interview with Hanh. I tried to wash the dishes with care, noting the feel of the water on my hands, the soap suds as they moved through my fingers. At some point, I spaced out. A plate fell from my grasp and shattered in the sink.

The next day’s meditation was more successful, though Hanh probably wouldn’t have liked me using that word. It lasted too long—an hour, I’d realized the previous day—but for snatches of it, a warmth surged pleasantly through me. The relief was immense. My thoughts ceased. A soothing disconnection separated me from the world.

Afterward, while the nuns worked and I wrote and even during lunch, my hearing felt sharper. The clink of chopsticks on enamel. The chomp of a piece of broccoli.

Time seemed to slow, yet I experienced no boredom. Just walking was interesting. The feel of my feet against the ground, the earth, as Hanh referred to it: heel-toe, heel-toe.

Again, we sat in the meeting hall and watched a videotape of one of Hanh’s talks. This one was humorous with a long digression—or maybe it was the point—about jealousy and measuring oneself against others and revenge. In it, he spoke of his left hand never envying his right hand even though his right hand gets to do so much more. His left hand doesn’t resent his right hand when hammering a nail and the hammer slips. The left hand doesn’t ask for the hammer to seek revenge. Later, Hanh spoke of the womb, how comfortable we were there: The weather was perfect.

Mindfulness was working for me. I felt lighter, no longer empty. I also felt a part of the sangha, the community there. The nuns were friendly though not gregarious.

Most were Vietnamese. In the States, meditation was very, very white, packaged as the answer to the worldly concerns of a certain stratum of American society. The scholar Jeff Wilson had observed how mindfulness meditation was stripped of its Indian roots to be applied to “the worldly cultural concerns of Americans, especially those in the middle-class, mainly white communities that have dominated the public conversation over what American Buddhism should be.” (131) We’d made meditation into a secular practice for the privileged.

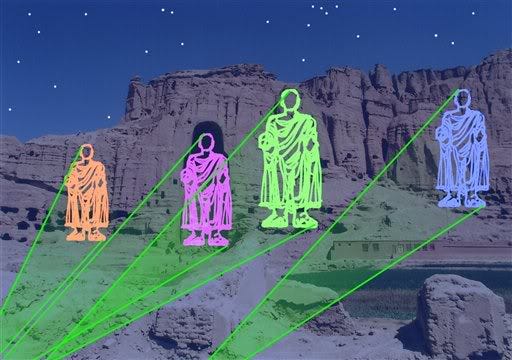

According to the sutras, the Buddha never meant for any of us to meditate. Meditation wasn’t intended for lay practitioners or the general public; it was strictly monks-only. It was meant to induce trance-like states on a monk’s path to enlightenment. In the sutras, the Buddha tells his monks as much. (See the Satipatthana Sutra.) Meditation has traditionally been a way to distance oneself from the world, not “get happy” in it. For monks, disassociation and even pain were an integral part of a meditation practice that led to nirvana. Mindfulness had become “McMindfulness,” a term coined by the Buddhist teacher Miles Neale, a commodified technique without a moral compass or ethical dimension.

After dinner, I expected to be approached about my interview. I finally asked one of the nuns, Sister Pine. She looked surprised. Hanh was ill.

Concerned, given that he was in his late eighties, I asked what kind of illness. “A cold,” she said. No one was permitted to see him.

I’m supposed to interview him.

Her eyes glinted in the light as she said she knew nothing about it. I’d have to speak to Sister Chân Không, Hanh’s second-in-command.

I asked where I could find her.

“Oh,” Sister Pine said, “she’s gone on a visit to the city and won’t be back for two days.”

The next afternoon, the lightness I’d felt was gone. The familiar black mass in my stomach had returned. I’d made it through the morning meditation with my eyes open. Later, in my room, I stared listlessly into space. I didn’t go down to lunch.

I fell in with the wrong crowd. Well, the wrong person. I attracted, perhaps, the only unhappy nun—a German—in all of Plum Village.

On my way to the meeting hall to watch, I assumed, yet another recorded video of Hanh, she sidled up beside me.

By the next day, it was clear that I wasn’t going to get to meet with Hanh. No one had spoken to me about it. No one I asked knew anything about my supposed interview. It was my second-to-last full day at the monastery.

I decided to get what I really came for: a cure. Meditation had worked that one day. Certainly it would work again.

The inverted U-shaped trajectory said otherwise. According to the scientific principle, positive effects inevitably turn negative. But I didn’t know that then.

During the nightly meditation, I decided to join the other nuns. I closed my eyes and focused on my breathing. After some time of watching my breath, a flash of blue passed across my field of vision. A white streak. Then a burst of red tendriled light like a firework.

In the nineteenth century, scientists called these visual phenomena eigenlicht of the retina. At the time, they believed these light shows were the result of external light playing off the eyelid, but an American physician later proved that the spots and figures—chaotic, nonsensical, sometimes rhythmic—came from inside us—from our memories, dreams, and experiences. They renamed them phosphenes.

From across the room came a cough. The phosphenes returned—a chrysanthemum of orange light became a new wave of warmth that surged through me. The warm feeling collided with the sensation that I was watching myself from across the room, observing myself—confused, afraid. The spiral of selves continued, one on another, interrupted by cherry bombs of light, burning.

Next to me, a nun’s breathing was steady. I counted my breaths until a vibration swelled in my chest. Like warmth, it moved through my stomach, back up through my chest, to my neck, then to my head. My body seemed to disappear.

Open your eyes, I thought. But I didn’t open my eyes. The red lights moved closer. My heart beat in my ears. Then there was no beat. My stomach contracted and something like fear entered my bowels.

A scream. It wasn’t a scream. Scream was a thought. I took a breath, but it locked in my esophagus.

Sweat pooled under my arms. Another rush of panic. I leaned forward and, breaking the spell, opened my eyes. I tried to stand. I almost fell back but caught myself. Around me, the nuns stared ahead, their faces serene, youthful. Panic returned, closed in.

I rushed outside. When the night air hit me, I took a deep breath. Barely air. Orion’s belt dotted the black sky. No moon. Just space.

I didn’t yet know that I was one of the 25 percent or 60 percent of people (depending on the study) that had an adverse reaction to meditation. Meditation didn’t actually agree with me. Until that night, I wasn’t aware that meditation could be a little hell, turning me into a bundle of nervous energy inside a ball of unsettling hopelessness.

Later I’d learn that I suffered from UEs, a polite acronym for the adverse reactions some meditators experience: unwanted effects. The effects reported aren’t minor: confusion, disorientation, dependence on the practice, anxiety, psychosis, deliriums, hallucinations, physical pain, sensorial dysfunction, exacerbation of neuromuscular and joint diseases, reduction in appetite, and insomnia.

Adverse side effects to meditation were well known in the medical community. As early as 1976, Arnold Lazarus and Albert Ellis, the co-founders of the psychological treatment known as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, expressed concerns about “prescribing” meditation: “[Meditation] is not a panacea. In fact, when used indiscriminately, there are clinical indications that the procedure can precipitate serious psychiatric problems such as depression, agitation, and even schizophrenic decompensation.” In 1984, other researchers published accounts of people reacting adversely to meditation. In the scattering of cases presented, all of the subjects experienced psychosis. A 1992 study of long-term meditators found that 63 percent experienced adverse effects. A 2012 meta-

analysis examined the flaws in studies of mindfulness-based and other meditation practices.

More studies would follow. In 2014, a study would show that the majority of subjects experienced negative side effects ranging from anger, anxiety, and psychotic breakdown. A 2017 study would document that 25 percent of people who meditated experienced unwanted effects, including panic attacks and depression.

The study accounted for varying types of meditation practices: focused attention (on an object or “being mindful”), open monitoring (letting thoughts float by), body awareness (body scans and relaxation techniques), imagination (picturing yourself in a peaceful place), and other informal practices. It also accounted for gender, race, nationality, education level, and context (where the meditation practice was learned and conducted, e.g., by a secular or spiritual teacher or self-taught). It also conducted a literature review that showed that the studies so often cited in the media hadn’t measured adverse effects and only looked at the supposed benefits of meditation.

The media loved studies that made meditation seem like it was right for anyone with any ailment. Rarely did studies that showed the negative side effects make it into the mainstream press. A Google search for the benefits of meditation garnered 148,000,000 results whereas negative effects produced a scant 650,000. I wasn’t aware of online forums like the Hamilton Project where people who’d experienced the negative effects of meditation gathered to share their often harrowing experiences.

Some refer to it as a spiritual crisis, the same kind that led St. John of the Cross to a union with God. In terms of meditation, all things cross, arise, and pass away. A serious practitioner invites darkness, hopelessness, and despair. The practitioner awakens to impermanence, the absurdity and unreality in all things, even the self. It can be a life-changing experience for the good, but it’s meant for monks with specific training who’ve had guidance and know how to handle it. For most, it’s a deeply unpleasant experience that can end very badly.

Many people think of meditation as an ancient spiritual healing practice. Within that practice occurs a shift in understanding. Though focusing on the present moment may seem like a harmless realignment of the relationship between the self and the world, if one follows it to its natural conclusion, “presentness” ends in the dissolution of selfhood. Where once was the “I” is only emptiness, a void. If one were to read Pema Chodron, the American Tibetan Buddhist nun and bestselling author of When Things Fall Apart, they’d assume that was a good thing. But researchers, like Britton Willoughby of Brown University, have found that it can be entirely distressing.

As I stood outside, looking up at the night sky, into outer space, I wanted to go home.

Hanh didn’t promote the medical model of meditation. He didn’t see mindfulness as a means to an end; it was the means and there was no end.

The medical model was made famous by John Kabat-Zinn—an academic, not an M.D.— who was also considered one of the founders of the mindfulness movement. Kabat-Zinn started the Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program in 1979 and was the first to tout mindfulness as a treatment for everything from overeating to cancer. (Kabat-Zinn did study with Hanh at the Providence Zen Center in the 1970s.) Because of Kabat-Zinn, meditation techniques were sold to Americans as the cure for everything from blood pressure to irritable bowel syndrome to insomnia to anxiety. It could curb addictions, treat mental illness, and remedy physical illnesses that traditional medicine had failed to cure.

Where Kabat-Zinn talked science and research, Hanh used the term “the path.” The point of the path wasn’t to get anywhere; the point was the path (referred to by Buddhists as the noble eightfold path). On it, practitioners tried to live by noble means: right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood (possessing only what is essential), right effort, right mindfulness (adopting Buddhist teachings), and right insight. Hanh’s teachings still existed within a Buddhist framework. Of the two Buddhist traditions—Mahayana East Asian (emptiness and interconnectedness) and Theravada Southeast Asian (transcendence in the everyday)—he drew on both. One should have a personal meditation practice and engage mindfully with the world “with every step.”

He talked about mental illness but not as a medical condition. To Hanh, a mental illness arose when the mind lacked “circulation.” Anxiety, depression, even psychosis—which he referred to as “mental formations”— resulted when emotions like anger and sorrow aren’t allowed to “come up” and be embraced. We all have an inner child who may be storing up a “seed” of resentment or fear. Mindfulness, or being present, allows us to notice the seed but not water it.

On my final afternoon at the monastery, still shaken from the night before, I participated in “working meditation,” which entailed shoveling gravel to fill the potholes in the driveway. I was putting away my shovel when a tall woman with long black hair approached me. She wasn’t much taller than I was but seemed to loom above. Her power was that great.

She introduced herself as Sister Chân Không. With one finger, she beckoned for me to follow her. At the main house, a van was waiting. She allowed me to go upstairs to get my recorder—a tiny MP3—and microphone.

Hanh’s home was little more than a shack. Outside stood bodyguards—monks, yes, but clearly Hanh’s protectors against whom I didn’t know. They let me pass without frisking me.

Inside was a desk with a dimly lit lamp on it. On the other side of the room was a small bed—a cot, really—and a nightstand on which sat a book. It had no comforter, just a brown wool blanket. A thin flat pillow rested near the head.

Sister Chân Không motioned for me to sit. A young monk entered the room. He carried a tray on which were two cups of tea. He placed one in front of Sister Chân Không and one in front of me.

We waited for some time. Then came a noise. A door opened and closed.

It would be hyperbolic to say that Hanh seemed to float, not walk. Hanh seemed to float, not walk. It would be ridiculous to describe his face as “glowing.” His face glowed. And his eyes. Strength seemed to beam out of them. And softness too.

He asked about me. I’d learned early in my interviewing career how to absent myself, Zen- out, make myself invisible. An interview wasn’t a conversation; it was an opportunity for the interviewee to speak.

I countered with questions, though not aggressively. He spoke slowly, unhurriedly. Again, it was as if different spaces existed between his words than for the rest of us.

At the end of our interview, I considered telling him about my negative experience. The urge came and went. I assumed something was wrong with me.

We stood. As I put on my coat to leave, he said, “You should stay. You belong here.”

The next day I left Plum village. As soon as I returned home, I transcribed the interview, edited it, and sent it to the editors. Their reply took months. It wasn’t quite right for them.

Years later, I’d see a photo of Hanh in a wheelchair after his stroke, which would leave him partially paralyzed. In the images of him after he’d woken from a seven-week coma, his face would be gaunt and wan. I’d read that he’d lost the ability to speak.

One year after that, my computer would crash, and I’d lose the audio file with Hanh’s watery voice on it. Gone would also be the only written copy of the unpublished interview. Into the ether it would go. Into space.

This post is in memory of Thich Nhat Hanh, who passed away this month. Readers like you make my work possible. Support independent journalism by becoming a paid subscriber. For $30/year, the price of a hardcover book, you help me continue to bring my writing to readers all over the world.

Buy Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses, my memoir now out from HarperCollins: