This post is part of the accompanying tips, resources, interviews with experts, and stories of recovery included in the exclusive serialization of Cured: The Memoir.

I want to gush when I write or talk to people about warmlines. They’re so necessary, especially right now and yet few people know about them.

Ultimately designed to provide preventative care, they’re for those experiencing mental and emotional distress who aren’t necessarily in crisis. Distress applies to a range of situations:

needing someone to talk to,

experiencing thoughts and emotions that have led to crises in the past,

having exhibited unwanted behaviors, and

needing resources (including those for trauma, domestic violence, being unhoused, etc.).

Perhaps most importantly, warmlines offer those who often don’t have access to services (e.g., people of color and those who are economically marginalized) the chance to get support. They’re also free.

When you call a warmline, you’ll be connected to a peer or counselor as soon as possible. A peer is someone who’s recovered from a psychiatric illness; they’ve been well-trained. They won’t judge or lecture or give you advice. They’re there to listen, perhaps offer their experience if it seems appropriate or you ask, give you resources if needed, and help you plan your next steps.

Each organization takes a different approach and sometimes outlines what to expect on its website. The Warmline, Inc. makes its policies and philosophy clear:

We are here to offer support.

Callers are allowed 2 calls per evening to the support line.

Calls last 15 minutes.

Exceptions are made when callers need extra support based on the subject of the call and our call volume.

We are open from 6pm-10pm Central standard time,

7 days a week. We occasionally observe holidays for self-care.

A vocal minority criticizes warmlines and warns people that call centers will notify emergency services if they think you are a danger to yourself or others. This is rarely the case. A 2021 study found this occurred in less than 1 percent of calls and that some warmlines have a policy against calling 911. We know that 911 and emergency rooms—though valuable in some cases—can lead to violence, forced treatment, and involuntary hospitalizations, which risk traumatizing or endangering those in crisis and worsening the situation. I want to stress that this isn’t the fault of emergency services or ERs; they aren’t, for the most part, trained to support people with mental health conditions.

You can find a local warmline by visiting the directory here.

I’ll provide more resources for warmlines like those that offer support to specific groups (people of color, the LGBTQ community, indigenous peoples—there’s even one for graduate students).

To learn more about warmlines, you can read this thorough article by Ashley Broadwater: “Need Mental Health Help But You Aren't In Crisis? Try A ‘Warmline.’”

Readers like you make my work possible. Support independent journalism by becoming a paid subscriber for $30/year, the equivalent price of a hardcover book.

Visit the Table of Contents and Introduction of Cured:

Find more resources for mental health recovery.

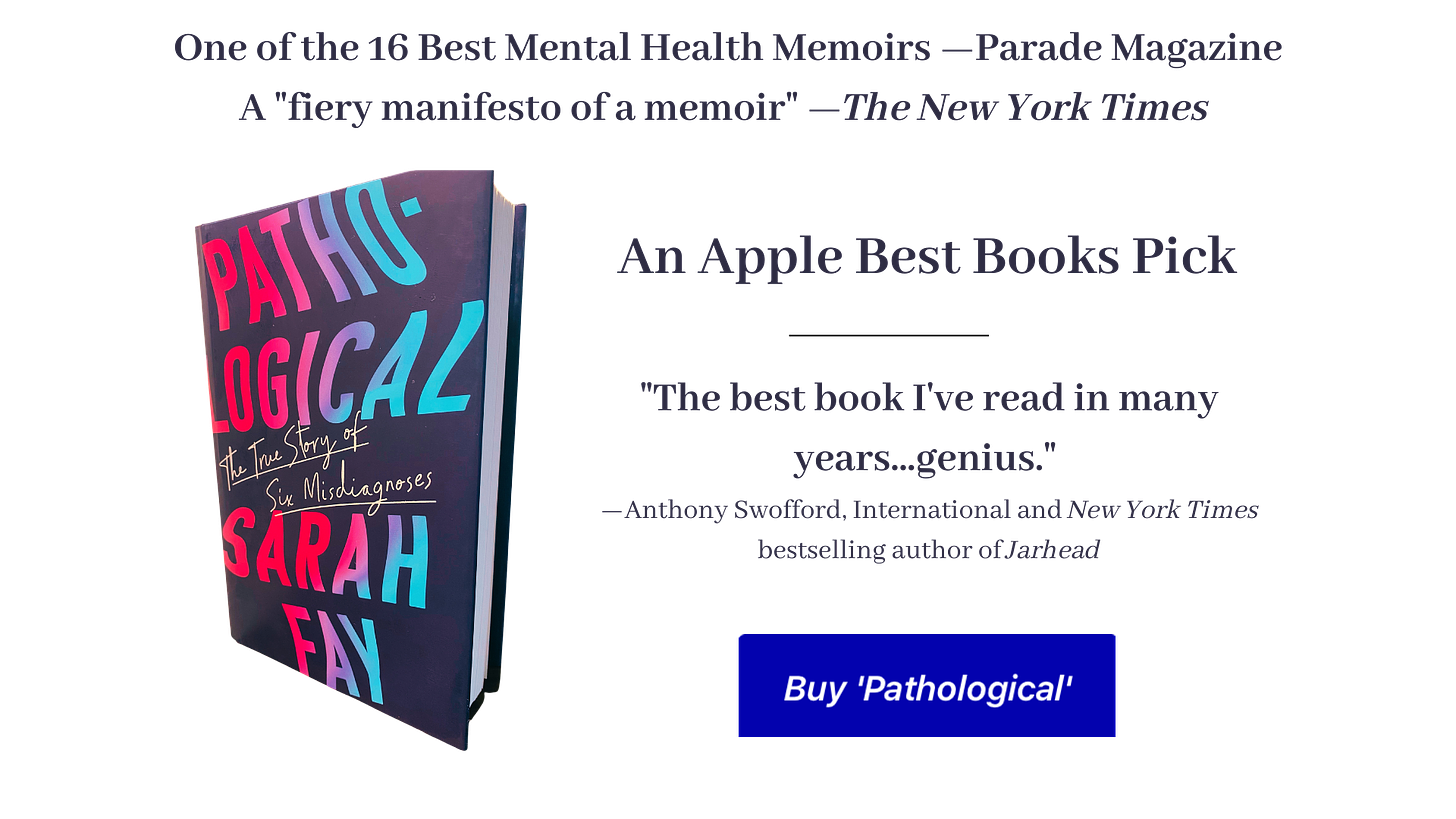

Read the prequel to ‘Cured,’ ‘Pathological’ (HarperCollins):

Warmlines and hotlines have been a great help to me. They've never contacted law enforcement to conduct a welfare check or anything like that before. The only time that happened was when I called 911 myself. I think a lot of the rhetoric surrounding crisis services lately is incredibly misleading and is causing some people to avoid utilizing these resources out of fear and it's upsetting to me.