The more! of friendship

Accepted more!: People should have friends—lots and lots and lots of friends. Human friends.

I ran up against this cultural more! of friendship two weeks ago, when I was featured on NPR. The episode “The New Mental Health Landscape” is excellent—and I’m not just saying that because I appear in it around minute 22:00. It’s a look at where we’re headed in an age of mental health influencers, medication shortages, and (this is where I come in) our continued use of scientifically invalid and largely unreliable psychiatric diagnoses and failure to give people hope of recovery.

My segment, which runs about five minutes, focuses on my first memoir Pathological (flawed diagnoses) and my second Cured (hope of mental health recovery).

But then it concludes with this about how I healed from serious mental illness:

“[Sarah] accepted that she did not want a romantic relationship—her family and cats are her social and emotional support.”

It can be shocking to hear yourself reflected back to you. Really? Cats? Where are her friends? Except the her is me.

Before we go any further, let’s get two things straight. When you announce on National Public Radio that your cats are your primary social support, you’ve crossed over into full-on cat lady. There’s no turning back. You can just throw away the lint brush and stop pretending, head out into the world unafraid of the cat hair blanketing your clothes.

And although there’s nothing wrong with relying on family and cats instead of friends per se, the selection of said family and cats over friends does have a bit of the socially maladjusted about it. True, having strong familial relationships can be a sign of maturity and emotional support animals and all that, but to many, not having a gaggle of gals or a group of guys signals a deficiency.

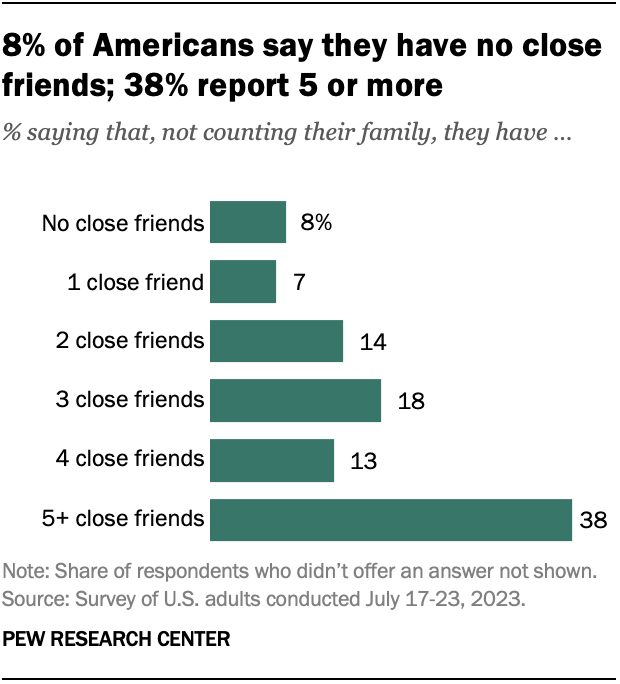

Someone without close friends is strange, suspect, and/or inept—at least in the U.S. These judgments and beliefs seem to transcend race, sexuality, gender, age, class, and ethnicity. When you look at the result of this 2023 Pew Research Study, what do you think and feel when you read that 8 percent statistic?

Maybe it didn’t evoke a response, but more than a few of you might have felt something akin to pity, sympathy, or maybe even a tinge of repulsion for the friendless.

I max out at about one close friend. Even as a child, I needed just one. And I chose that friend carefully.

One-friending became a lifelong practice. Yes, there were periods when I was part of a group though not for long. I’ve spent years without any close friends either because they were replaced by romantic partners (something Americans have been trending toward since the 1990s) or I just didn’t seek them out.

But I always felt like I had to have friends.

The media tells us that having friends leads to better health and a better life: stress reduction, a positive outlook, and longevity. One social scientist says that having friends—plural—is “as important as diet and exercise.”

The number of friends one has is the litmus test of one’s worth, sanity, and likability—a test I seemed to fail, especially when I believed I should have friends and was struggling with serious mental illness.

It took my recovery to realize that—supposed health risks be damned—close friends just aren’t my thing. Facebook posts. BFFs. Glasses of wine and nights out. Listening to someone vent. Friendship bracelets. Not for me.

Not even a supposed “soul friendship,” which strikes me as little more than being friends with someone who isn’t an asshole. (They’re supportive, honest, don’t criticize you, are there for you.)

Probably not even a “true friendship,” the kind espoused by Aristotle and Michel de Montaigne and others, one that’s without motive so unlike many contemporary friendships. Today, a friend is someone who’ll be there to drive you to the hospital or who you go to the movies with or just laugh with. That’s what Aristotle called friendships of utility and pleasure. A true friendship is one based on virtue, i.e., two people attracted to each other’s goodness—and that’s it. No brunches or bridal showers required.

(In case you’re wondering, no, your romantic partnership isn’t a true friendship because marriage is contractual. Family is out because those relationships have an unbalanced power dynamic.)

I’m not against friendship; my particular penchant is for virtual friendships. (Love my Substack friends and all of you, members of the Less and Less community!)

It’s just that my need for connection is easily satisfied—largely because I’m the most fun person I know. I always want to do exactly what I want to do. There’s no conflict, and I never have to settle. I’m reliable. It’s impossible for me to show up late because I’m always with me. I tell myself what to do but in a supportive way.

Put a cat or two in the room and, my friends, we have entered heaven. Heav-an.

What if humans aren’t actually predisposed to have friends?

Friendship evangelists claim that humans are biologically predisposed to having friends. This claim relies on the anthropomorphic application of the term “friendship” to baboons, chimpanzees, elephants, horses, etc.

But does “friendship” exist in the animal kingdom? Not exactly. Having allies is evolutionarily beneficial to the species—it can help you acquire food, shelter, protection, and dominance—but using terms like “friend” (“one attached to another by affection or esteem”) to describe that allyship is shaky. Animals do become attached and show affection, but esteem is a human emotion.

If we use the secondary definition of friendship—“one that is not hostile”—then yes, animals have friendships and that means we probably should have more of those kinds of friendships too.

The friendship crisis that’s really a blessing

The prevailing message is that Americans are in a “friendship recession,” a “friendship crisis.” We must have someone to rely on, to listen to us, to call, to celebrate our birthdays with, to arrange playdates with so our children won’t come across as little people who can’t make friends.

But—

What if this supposed friendship crisis is a good thing?

What if having fewer friends, when our lives are already too full, relieves stress and makes us healthier?

What if instead of obsessing over friendships, we embraced acquaintanceships and interactions with strangers?

What if we assumed that a “loner” must just love being in their own company?

What if we remove the pressure to have lots of friends—a pressure that can lead us to accept friendships that aren’t good for us and stress us out?

I love that we’re allowed to have no friends or one distant friend or one close friend and not be seen as a social pariah. That we can cycle through friends and not appear fickle or “bad” at relationships. A friendship can run its course, be complete, and we can move on.

The capital-T truth is that feeling connected and experiencing joy don’t come from friends or romantic partners or any other source; only from ourselves—whether we’re in a room full of people or family or cats.

Not having friends doesn’t make us sad, lonely, or scared. The belief that we should have them or are somehow inadequate for not having them does. Let’s have less of that.

In lessness,

Sarah

p.s. Next week, we come together for our first Less-in where we’ll introduce ourselves and talk about something we could do with a little less of in our lives.

Get the discounted annual subscription ($30) to join the Less of More and More community to explore our culture of too much and how, maybe, having less can bring more ease, peace, and serenity—plus, get the serialization and audio of Cured: The Memoir, my story of recovery from serious mental illness and the sequel to Pathological (HarperCollins).

Sarah, you’re preaching to the converted - sort of. I agree, the constant push to have lots of friends is the usual pop media conventional wisdom about what “everyone” needs. I’ve always framed this as an introvert/extrovert thing - but also as me having a finite well of attention for tending to myself and others. I’ve become more distractible with age, and I consciously limit social interactions, especially during the week.

But (counterpoint 1): I’m not teaching this semester, so I have more attention to give friends - and I find this very satisfying.

And (counterpoint 2): I’m in that 38% of the Pew survey who have 5 or more close friends, and in part that’s because these longtime friends function as family for me, my husband, and son. We don’t have a bio network to rely on. I think everyone does need support networks of some sort, even if they’re just one or two people.

Lastly (counterpoint 3): virtual connections can feed a lot of the need for emotional connection - and I know how lively and engaged you are in such settings 😉 The thing is, such virtuality can be turned on and off at will. While controlling the amount of connection we have can be positive (especially for women), I’m also in favor of the serendipity and stuff I can’t always control in real life.

Hi, Sarah, I'm all in on the Lesser-More mission! As someone who has spent a lot of time thinking about, studying, and writing about friendship, I think you've brought up so many valid and important points! Ultimately, each of us wants to build a life that is meaningful and satisfying TO US, and that looks different for different people. We absolutely need to question our shoulds!

Not all friendships are up-lifting. Having more friends isn't necessarily better. Not everyone has to be a life-of-the-party extravert!

Friendship can also take many forms, ranging from more intimate to more casual, and focused on different activities or situations or phases of our lives. All of these can have value. Many friendships don't last forever.

Relationships take time and effort. And yet... Friends can make the good times more fun and the hard times easier to bear. They can be a life line, particularly when family support is lacking. It feels good to be known and valued.

Interestingly, research suggests that one reason older people tend to be happier is that they're pickier about who they spend their time with!