*This is written in response to yesterday’s publication of the latest edition of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), psychiatry’s “bible.”

The answer is yes and no.

If you’ve often heard this and not known exactly what is meant, you’re not alone. If you’ve never heard it and don’t know what is meant, you’re also not alone. The “bible” referenced is The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—the manual from which all mental health diagnoses come: social anxiety disorder, autism, schizophrenia, binge-eating disorder, etc. The metaphor might offend some people, which is understandable. Think of it not as a comparison to the Holy Bible but to a lowercase-b bible in the sense of an authoritative text.

Whether or not you’ve heard of it, the DSM holds sway over hundreds of millions of people’s lives, specifically, the 46 percent of American adults and 20 percent of American children and adolescents who will receive a mental health diagnosis in their lifetimes. That number topples over into the billions if we include the parents, loved ones, friends, teachers, colleagues, physicians, bosses, children, and coworkers of that 46 percent of adults and 20 percent of children and young people.

It may surprise some to learn that the diagnoses contained in the DSM are entirely hypothetical. They’re based on theories, not legitimate scientific findings. (Exceptions are dementia and rare chromosomal disorders.) Its title may sound scientific—diagnostic, statistical—but the DSM is written by a small, select group of mental health professionals, many with financial and personal conflicts of interest with Big Pharma based on their opinions and ideas. Most of the DSM’s authors are members of the American Psychiatric Association (APA)—a private professional organization, not an independent medical or scientific group. The APA publishes and profits from the DSM. The 2013 edition of the DSM brought in $20 million in its first year.

Facts about the DSM

It started in 1952 with the first edition, the DSM-I.

Each edition is marked by a Roman numeral (DSM-I, DSM-II, etc.), except the DSM-5, which returned to Arabic numerals originally to be able to offer the more techie-seeming DSM-5.1, 5.2, etc.

The most recent edition (DSM-5-TR—TR for text revision) came out this month (March 2022) and is the first full-text revision in nearly a decade.

The DSM’s diagnostic codes (e.g., 296.20-296.36 for depression) are used by clinicians (physicians, psychologists, social workers, therapists) to get reimbursed by insurance companies, people to receive disability and educational services, and the legal system to settle questions of a person’s competence and/or sanity.

Over the various editions, the number of diagnoses and spectrums and subtypes has swelled from 128 in the first edition published in 1952 to 541 published in the fifth edition in 2013. In the newest edition, that number now hovers around 544. (There’s no agreement on the exact number of diagnoses. Some say over three hundred, others over two hundred. It depends on whether you count subtypes and catch-all categories.)

The authors of the DSM created and create “mental disorders” how they see fit.

In the current edition, personality and context aren’t taken into account. For instance, if someone experiences grief after say, having lost one’s job, it isn’t necessarily considered a reasonable response to the situation; the person can be given a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD).

The DSM’s authors have historically been cisgender, heterosexual, white men.

It offers no advice in terms of treatment.

It was originally published to give hospital psychiatrists a common language when referring to patients—not for patients to use to diagnose themselves or each other and certainly not as a way for patients to think of themselves and others.

In the DSM, each diagnosis consists of a list of symptoms. If a person has x number of symptoms, that person qualifies for the diagnosis. For instance, if a person has five of nine symptoms listed under the diagnosis of depression (e.g., sadness, loss of interest, weight loss or weight gain, sleeping more than usual or having insomnia, an inability to concentrate), that person can be presumed to have depression. Those numbers are mostly arbitrary. One of the primary architects of the DSM was a man named Robert Spitzer. When asked why a person needed five of nine symptoms to get a depression diagnosis, Spitzer said, “It was just consensus. We would ask clinicians and researchers, ‘How many symptoms do you think patients ought to have before you give them a diagnosis of depression?’ And we came up with the arbitrary figure of five…. Because four just seemed like not enough. And six seemed like too much.”

The DSM is meant to but hasn’t been able to show the point at which normal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors cross over into abnormal. The DSM’s authors merely imagine the line between normality and abnormality.

DSM diagnoses are given without a test or scan or any other way to confirm the diagnosis. (Again, dementia and rare chromosomal disorders are exceptions.)

The DSM’s Authority

Although the facts about the DSM don’t instill a great deal of confidence, it has tremendous authority. Unlike in physical medicine, it is the only manual used in mental health. In physical medicine, doctors rely on various textbooks and manuals (and, from what I’ve read, studies and information found on the Internet). The Merck Manual is financed by pharma, but it’s free, unlike the DSM, which costs hundreds of dollars and is published by the APA for monetary gain. The Washington Manual is produced solely by academics, includes in-text citations citing every study on which a diagnosis is based, and uses a rigorous review process. The DSM has no in-text citations and an inadequate review process.

The DSM as a Work of Culture

Even if you’d never heard of the DSM before now (and many if not most people haven’t), it dictates how we think about our mental, emotional, and physical lives. It’s the reason emotions like depression and anxiety are used interchangeably with diagnoses of anxiety and depression (e.g., feeling anxious about attending social engagements after a year-and-a-half in quarantine equals social anxiety disorder instead of just understandable anxiety).

Our ideas and beliefs about mental disorders—“clinical” depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, etc.—shape how we view ourselves and treat each other. Yet despite the ubiquity of DSM diagnoses and the way they’ve seeped into our lives, much of what people believe about mental illness is false and stigmatizing: mental illness isn’t the result of bad character, a chemical imbalance in the brain, how we were raised, stress, genetics, or God’s will.

The DSM’s Flaws

Some of the most prominent psychiatrists have denounced the current DSM and urged medical schools, clinicians, and the public not to trust it.

That’s because DSM diagnoses are scientifically invalid and largely unreliable. Invalidity means they have no objective measure; they’re based entirely on self-reported symptoms and a clinician’s opinion. Reliability means that using the DSM, clinicians can’t agree on the same diagnosis for the same patient even if they see that patient at the same time. Former Director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Steven Hyman put it best. He called DSM diagnoses little more than “fictive categories” and the DSM “an absolute scientific nightmare.”

The DSM doesn’t tell us what a mental disorder is. It doesn’t provide a measure by which to gauge if a person’s symptoms are severe enough to qualify for a disorder. As Allen Frances, who directed the DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR task forces and later came out against the DSM, said: “There is no definition of a mental disorder. It’s bullshit. I mean, you just can’t define it.”

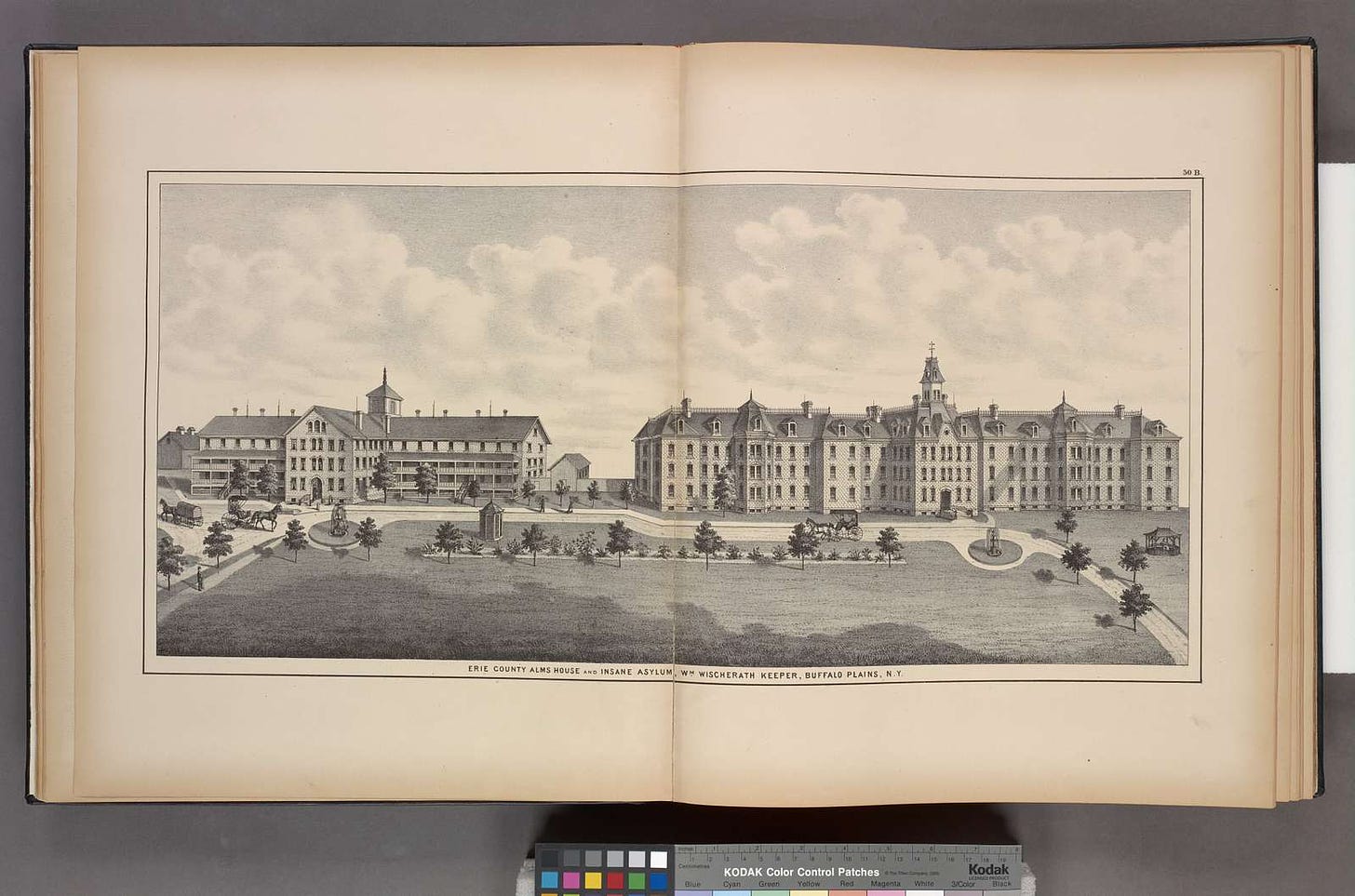

Metropolitan Lunatic Asylum, Kew, Victoria (Australia): boys walking along a ladder laid upon the floor Still a bible, of sorts

Some clinicians say they no longer use the DSM (which is frightening because what are they basing their diagnoses on?), so the DSM may not be psychiatry’s bible in the sense that everyone follows it to the letter. But it’s still a holy text. Psychiatry is well aware of the problems with the DSM and mental health diagnoses. Yet in the nine years between the DSM-5 and the full-text revision that came out this month, the APA conducted no significant reforms to nearly all diagnoses. So we’ll go on using it, incorporating it, seeing ourselves in it mainly because it’s been around for so long.

Support independent journalism. Readers like you make my work possible. Get the annual discounted subscription—about the equivalent of purchasing one hardcover book.

Purchase my memoir, Pathological: The True Story of Six Misdiagnoses (HarperCollins), here:

*