🎧 Listen to Sarah read this installment of Cured above.

Note: This chapter describes suicidality. If you’re having thoughts of suicide, speaking to someone can help. You aren’t alone. Call or text 988. If you don’t feel you’re a danger to yourself, call or text one of the many warmlines available to help.

My friend Lisa picks me up in her Subaru, and we drive to the suburbs. The idea is to get some things for my claustrophobic studio apartment to make it “homier.” Interior decoration appeals to me about as much as breaking a bone: painful at first and then just tedious.

But I want to be “normal.” After twenty-five years in the mental health system—an eternity, it seems now—my new psychiatrist has told me that recovery from psychiatric disorders is, in fact, possible, a secret none of the many clinicians I saw ever divulged. According to them, my diagnoses (I received six, one after another, trying to give a name to my mental and emotional pain) were lifelong. The best I could do was manage my symptoms. Now, I’m trying to heal inside a fantasy of what’s “normal” and what’s not.

We head west and eventually merge onto the highway. We’ve been friends for twenty years, ever since we both waited tables at the same restaurant. We fall in and out of touch. During one of my deepest depressions, I lived with her for about a month.

Lisa tells me her jewelry business is struggling. She’s dyed her dark hair blonde, which makes her perfect porcelain skin look even more flawless.

During a lull, I look out the window. The landscape seems to blur though Lisa isn’t driving that fast. Pressure builds in my chest. The pressure flutters, then tingles, then pulses.

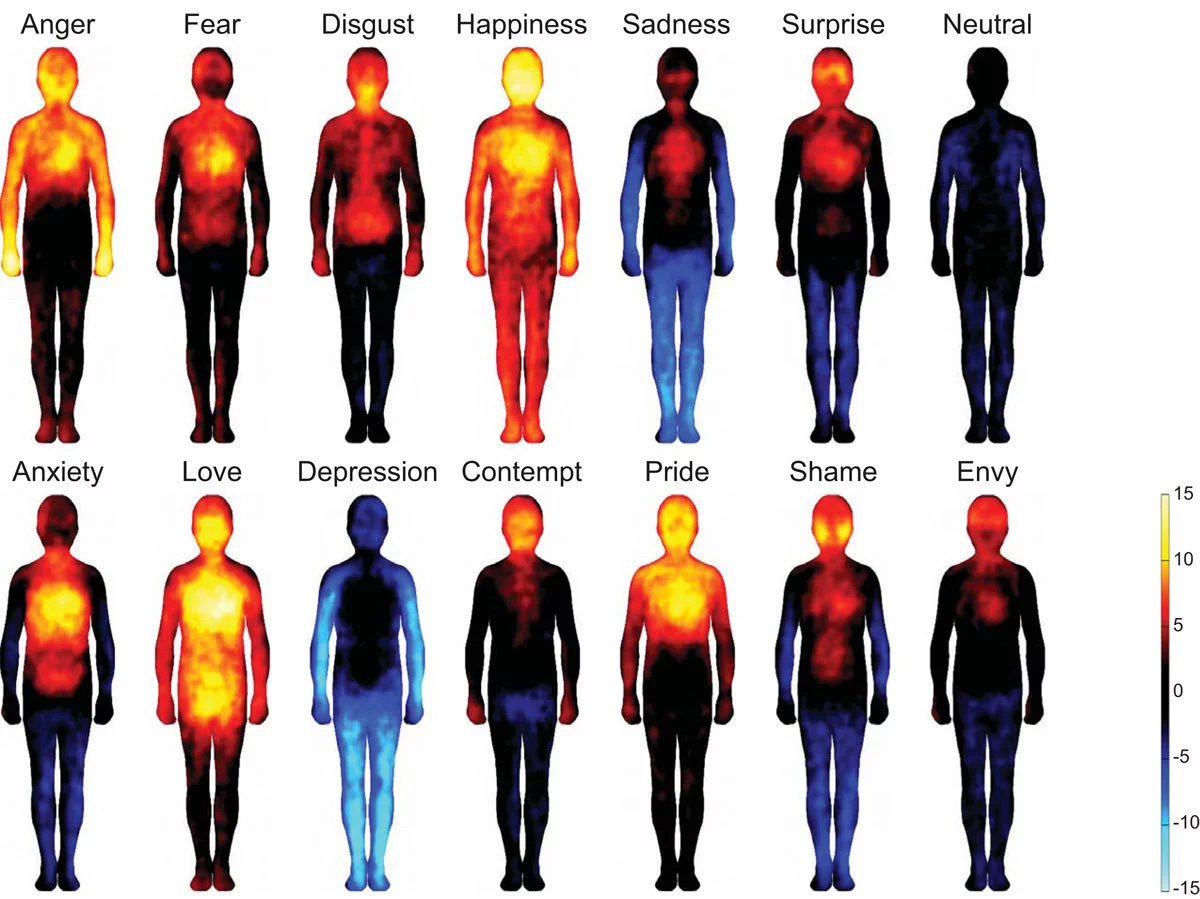

I couldn’t name it then, but that’s how anxiety and fear manifest in my body. The American Psychological Association (APA) describes an emotion as “a complex reaction pattern involving experiential, behavioral, and physiological elements.” Merriam-Webster defines it as “a conscious mental reaction…subjectively experienced as strong feeling…typically accompanied by physiological and behavioral changes in the body.” Some emotion theorists say we can physically map our emotions:

At the time, like many people, I didn’t even know that an emotion is a sensation or a series of vibrations in the body: a fluttering heart, sweaty hands, a stomachache, weak knees, a pulsing sensation in your head, heavy limbs, the tightening of your shoulders and neck, a rush of warmth to your face.

To read or listen to the complete Cured, choose the discounted annual subscription for $30—about the price of a hardcover book. Each purchase brings awareness to mental health recovery.

You can also gift ‘Cured’ to someone in need.